Providing a counterpoint to the soulless and monochromatic advocates of the period, the architect left an imprint on design with his fearless use of color and pattern.

Welcome to From the Archive, a look back at stories from Dwell’s past. This story previously appeared in the February 2008 issue.

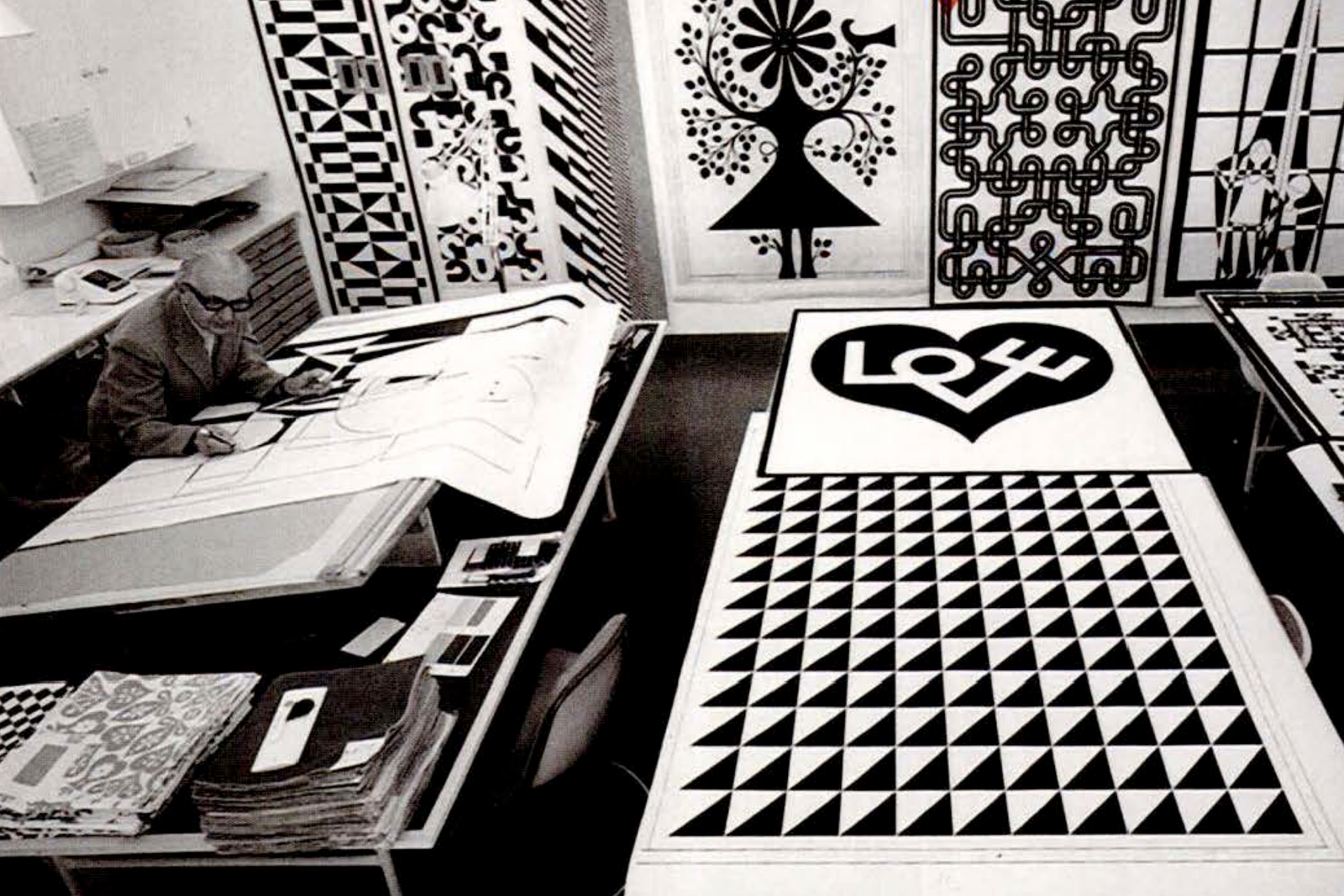

Imported from Europe in the black-and-white pages of design journals, modernism was often criticized as soulless and monochromatic—two charges that could never be leveled against Alexander Girard. The multitalented architect and designer succinctly defined his colorful, cluttered, and bold approach as "aesthetic functionalism," with the belief that delighting the senses was just as important a function of design as any other more practical concern. There is perhaps no greater evidence of this than in Girard’s love of "unrefined and unsophisticated" crafts, which he spent a lifetime accumulating from diverse corners of the globe. These crafts informed Girard’s sensual mutation of the International Style, culminating in an output that is wholly unique and instantly recognizable.

Girard’s appointment as the head of Herman Miller’s burgeoning textile division in 1951 initiated one of the most exuberant periods in modern design’s history. At Herman Miller, Girard joined design director George Nelson and designer Charles Eames to form an unrivaled triumvirate of creative power. Under founder D.J. De Pree, the company allowed the trio free rein, and in turn, the Big Three, created designs imbued with such richness that their resonance is as powerful today as ever. However, while Nelson and Eames never left the public eye, Girard’s contributions—more decorative, more ephemeral, and less well documented—had until recently largely faded into obscurity.

"He was a designer who didn’t fit in any particular category," notes Matthew Rembe, who directs the Girard estate for máXimo. The genre-defying scope and gargantuan mass of Girard’s output is indeed impossible to pigeonhole, ranging from homes to restaurants, furniture to branding, textiles to wallpaper, exhibitions to handicrafts. All the more impressive is the attention to minutiae and exacting precision Girard brought to each project. While the variety is astounding, the more time one spends examining his output, the less disparate it becomes, and the Girard-specific language that unites an interior design to a Mexican doll to a corporate installation grows clear.

Images courtesy Herman Miller Inc./Graphics by Alexander Girard

Girard’s most commonly acknowledged contribution to the canon of modernism, and a thread that binds everything he produced, was his fearless approach to color and pattern. From the inception of the textile and wallpaper program for Herman Miller, colors hitherto considered gauche—magenta, yellow, emerald green, crimson, orange—became a part of the company’s formal vocabulary and, in time, the world’s. As Girard recounted to fellow textile designer Jack Lenor Larsen in 1975, "The simple geometric patterns and brilliant primary color ranges came to be because of my own urgent need for them on current projects. As you will remember, primary colors were frowned upon in those days; so were geometric patterns. I had the notion then, and still do, that any form of representational pattern, when used on folded or draped fabric, became disturbingly distorted, and that, therefore, a geometric pattern was more appropriate for draped fabric. Also, I was against the concept that certain fabrics were ‘suited’ to certain specific uses—like pink for girls or blue for boys." To Girard, everything was fair game for interpretation and combination.

Over the course of his 22-year tenure with Herman Miller, Girard created hundreds of textiles, both solid and patterned, in a multitude of colorways and breadth of material. While his initial years with the company could largely be defined in a supporting role (his textiles created the backdrop and covering for Eames’s and Nelson’s furniture), by the late 1950s Girard’s talents were in full swing.

The 1958 design for Herman Miller’s Barbary Coast San Francisco showroom showcased Girard’s opulent tastes, and provided a clue as to the splendors that would unfold over the following decade. On a scouting trip to San Francisco, Girard, Eames, and Herman Miller’s Hugh De Pree (D.J.’s son) chanced upon a boarded-up building while searching for somewhere to have lunch. Taking a hammer and crowbar to the layers of plywood, they began to uncover what had once been a music hall of considerable ill repute, rife with life-size nude satyrs, nymphs, and all manner of marvelous ornamentation. At Girard’s behest Herman Miller secured the property, and he set about creating a thoroughly modern interior design that would complement the location. As Interiors noted at the time, "[Girard] has out-Victorianed his uninhibited predecessors with an application of gold leaf and blue, crimson, and violet paint that would make them swoon with envy." As Hugh De Pree would later attest, "Girard’s rare gift for excitement, detail, and color made the San Francisco showroom a brilliant polychromatic landmark."

Across the country, in New York City, Girard was working on a concurrent project that would focus all of his talents, and prove to be one of his most celebrated accomplishments. La Fonda Del Sol, a restaurant housed on the ground floor of the Time & Life Building, opened its doors in October 1960, inviting diners to be completely seduced by Girard’s abstracted vision of a Latin American-themed cantina. Girard designed everything from the space itself down to the matchbooks, and collaborated with Eames on a new seating design—a variation of the fiberglass shell chair with a lower back that wouldn’t obscure the place settings—which was upholstered in dozens of colors. The primary motif of the restaurant was the sun, drawn handsomely by Girard in a sequence of iterations that appeared on everything from the menus to the server carts to the washroom faucets (and most recently a 2004 line of Kate Spade handbags). One Eames Office employee remarked that the restaurant was so exciting to be in, she couldn’t eat. Sadly, it closed in 1974.

Images courtesy Máximo/Vitra Design Museum/Kelly-Mooney/Corbis

The short-lived Textiles and Objects (T&O) shop on Manhattan’s East 53rd Street, the culmination of a decade’s work with Herman Miller, was another of Girard’s great achievements. Like La Fonda Del Sol, T&O was conceived as a total environment, where the public could buy yardage of Girard’s fabric in addition to a hand-picked selection of folk crafts from around the world. Girard worked with Herman Miller to design the entire store, including all of the storage and display units. The store was an anomaly at the time, and didn’t attract the clientele Girard had hoped for. By 1963 it was closed. Marilyn Neuhart, who worked for both Charles and Ray Eames and Girard, and whose hand-sewn dolls were sold in the shop, described it as his baby, and in a 2003 interview commented, "After that, I don’t think he felt the same about Herman Miller."

However, Girard’s relationship with the company would continue for another decade, and in 1967 they introduced the Girard Group, a collection of some 25 chairs, sofas, ottomans, and coffee, end, and dining tables, originating from Girard’s total design for Braniff International Airways. While the designs have their merit, they almost seem like an excuse for extravagant uses of upholstery in customizable combinations. As Girard himself noted in the brochure, "The outer shell may be upholstered or painted and the welt selected in one of three coordinating colors. The inner shell and cushion may be upholstered in a variety of fabrics. The permutations are infinite." The lifespan of the collection, however, was not: It was canceled the following year. "I think it was a little head of its time," says Marilyn Neuhart. "You could mix and match [so many things] and I don’t think most people were equipped to make those kinds of judgments. It was just expensive to make and expensive to market, so Herman Miller was not terribly patient with it." Today existing examples are rare and highly sought after.

After a last hurrah designing so-called "Environment Enrichment Panels" for Herman Miller’s Action Office cubicles in the early 1970s, Girard retired to his home in Santa Fe, where he had lived with his wife Susan and their children Marshall and Sansi since the late 1950s. His beloved collection of over 100,000 pieces of folk art—or, as he liked to call them, "toys"—was thoroughly cataloged by the Girard Foundation and donated to the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe in 1978. The museum opened a Girard Wing in 1982 with a Girard-designed display of some 10,000 objects, a riot of color and seeming disorder underlined by an unseen precision. To this day it serves as an amazing, all-encompassing celebration of his life’s passion. Girard died in 1993, at age 86.

A 1963 memo entitled "Some Notes on the Folk Art in the Herman Miller Collection," which is attributed to Girard, contains a statement that, although referring to the subject at hand, serves as a poetic disclaimer for his own work as well: "The objects were not designed for deep contemplation but rather as simple expressions of delight, amusement or reverence. They were created by the spirit of the craftsman. Invented and fashioned by an individual for the enjoyment of others."

See more from the Dwell archive on US Modernist.

Related Reading:

This Michigan Couple Found Out They Own the Last Standing Home by Alexander Girard

From the Archive: The Lesser-Known, "Lone Wolf" Modernist Master You Should Know

No comments:

Post a Comment