Video games like "The Sims" have long allowed players to live out their homemaking desires. But elements from the genre have since made their way into other hugely popular series, often unexpectedly.

This story is part of Dwell’s yearlong 25th-anniversary celebration of the people, places, and ideas we’ve championed over the years.

Let’s say you commit a crime in Grand Theft Auto:

Robbing a bank, a cartoonish instance of vehicular manslaughter, a shakedown gone wrong—there are all types of options. With the police on your heels, you have no choice but to flee by heading to any car on the road, yanking the driver out of their seat, and speeding off. But where will you go? Good luck finding somewhere to hunker down inside. In a city full of buildings and doors, you’ll find that pretty much all of them are locked.

Ever since 2001, when Grand Theft Auto III brought virtual cities to life as "open worlds," the video-game genre—defined by the player’s ability to go almost anywhere in a cohesive large environment, as opposed to proceeding through a series of discreet levels—has largely focused on the public realm. In many open-world games, the built environment comprises largely flat textures, like Road Runner painting a tunnel on a rock wall. The ability to go indoors is often limited to cutscenes (prescripted events in which the player has no or severely limited control) or special one-time events. Players can swing the entire length of Manhattan in the Spider-Man games, for instance, but they can’t go into any of its bodegas. This is often a necessary limitation for technical and practical reasons. Just imagine how much manpower it would take to design every room in a single skyscraper or block in a city, in addition how much hard drive space it would take to house all of that data. Still, the lack of literal interiority can often align with a lack of figurative interiority. The lived environment says a lot about who people are and what their priorities are, and that perspective has, historically, been lacking in these types of games.

That has changed in the last few years, owing to both technical advances in what video games can allow players to do, and growing interest in games that allow players to express themselves through home design. What was once a standalone game genre unto itself is now an essential component of some of the most popular video games in the market. That substantial design modes have found their way into historical period pieces, soap opera melodramas, the nuclear postapocalypse, and galaxy-spanning sci-fi adventures is an obvious indication of the genre’s enduring appeal. More specifically, though, it can be seen as an indication of how game audiences are changing, and how quickly video-game technology is evolving. And perhaps most importantly, it offers another versatile toolkit to allow players to express themselves, not just through a limited set of actions, pre-canned dialogue, and avatars, but also through environmental storytelling. (An example of environmental storytelling, in which players intuit events, might be a room with a table and chairs knocked over haphazardly, as opposed to a character stating plainly, "There was a fight here.")

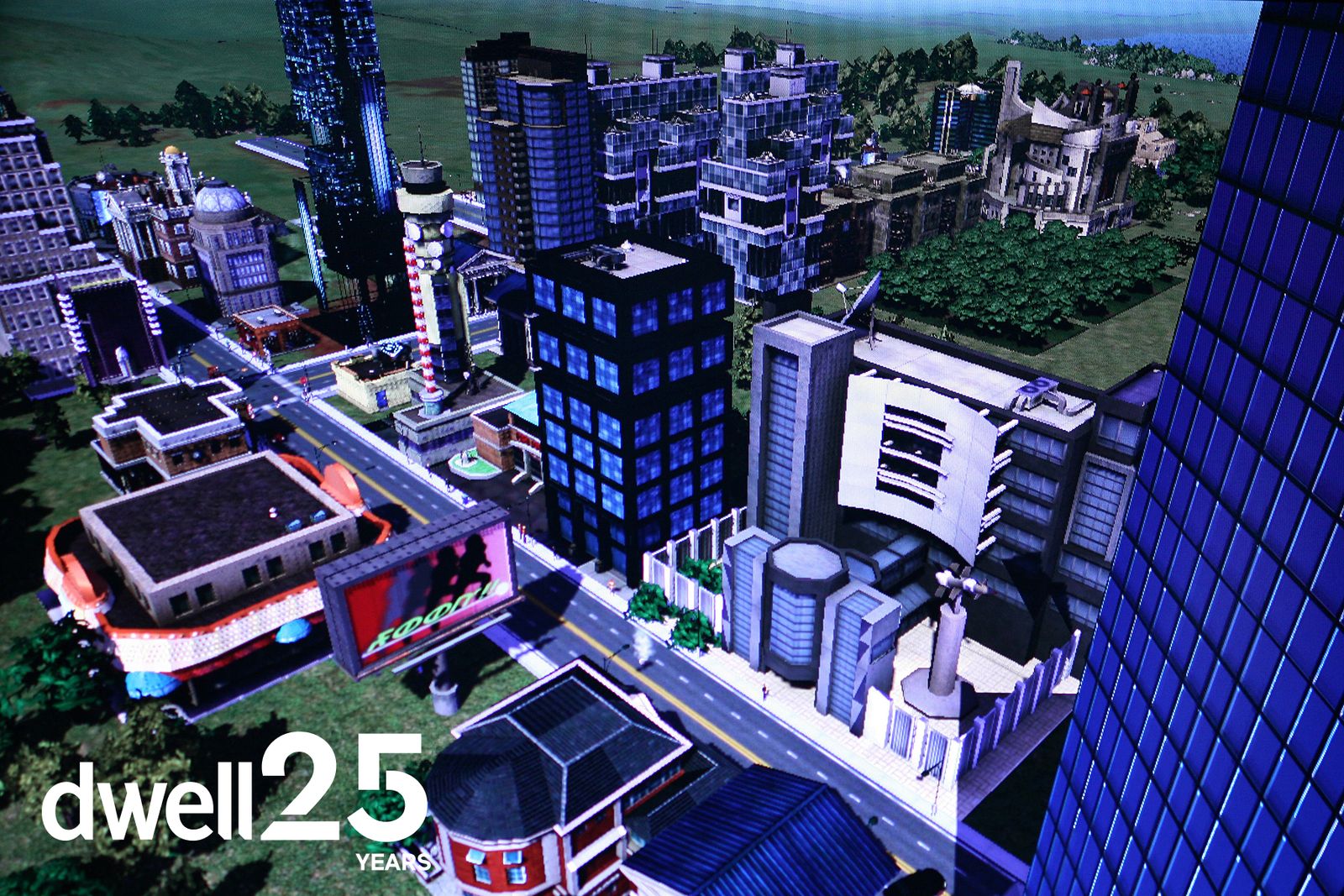

A scene from Grand Theft Auto III, one of the most popular video games of all time.

Courtesy Rockstar Games.

For decades, home design constituted a self-contained genre in video games. Early games—including ’90s stalwarts SimCity and Harvest Moon—allowed players to plan out their cities and farm, hop on the unending treadmill of maintaining a habitable living space, or a functional civic society. These games had relatively simplistic win states because, unlike conventional narratives with heroes and villains, the player’s motivation was self-evident to anyone with a pulse. To run a good city, you had to run a city with standard markers of competence, like functioning utilities and infrastructure not crippled by natural disaster. Being a good farmer meant running a farm with sufficient crop yield.

A few years later, the early 2000s brought games like The Sims and Animal Crossing, finally allowing players to go inside the homes of individual characters and make minute aesthetic decisions, like what furniture the residents did (or didn’t own), where doors went, and whether their swimming pools had ladders. These games helped draw a relationship between their character’s well-being and their home environment: Sims would get angry if their home was dirty, and Animal Crossing villagers would remark on the changing of seasons and related events, how frequently the player has logged in to check on their village, and the general state of upkeep (villagers are not fans of players who let weeds grow uninhibited). These games have spawned decades of imitators and evolutions around the design of a functioning society or domicile. The ultrapopular Stardew Valley (2016) was explicitly inspired by Harvest Moon’s calming gameplay loop of farm maintenance.

But games that prioritize letting players farm crops and lay out furniture are no longer the only titles that provide the opportunity. In the most recent Assassin’s Creed game, set in Sengoku-era Japan, players can design the layout of their hideout compound, choosing where buildings are located, drawing paths between them, planting trees, and placing animal friends around the grounds. In Like A Dragon: Infinite Wealth, the protagonist takes a lengthy sojourn to an island in a side quest that parodies Animal Crossing’s village-architect mandate. In Spiritfarer, a ferryman shepherding animals into the afterlife must also arrange each of their cabins so that everyone can fit on the boat. The development outfit Bethesda Game Studios, best known for enormous open-world role-playing games in the Fallout and Elder Scrolls series, has similarly caught the home-design bug. In its last two titles, 2015’s Fallout 4 and 2023’s Starfield, players gained the ability to not just buy a home for their character, but to also design every inch of it, devising not just floor plans and decor, but power grids and automated defenses as well. A feature whose customization options often amounted to "what color should the walls be?" just a few years ago has grown far more complex.

A still from the game Stardew Valley, which exploded in popularity during the pandemic.

Courtesy of Concerned Ape

In doing so, these games have grown beyond the diorama type of interactions that can often typify video games. Allowing players to nitpick the details of their virtual spaces changes how they perform in social spaces, whether they’re nonplayable characters (NPCs) or other players online. In their 2007 paper on social norms in The Sims Online, a multiplayer version of the normally single-player Sims experience in which players can interact directly with each other, the academics Rosa Mikeal Martey and Jennifer Stromer-Galley observed that "the house also creates a metaphorical space in which players use offline notions of expected behavior to guide their actions as hosts and visitors." In other words, players fall into role-play based on the "environments" that they are in. Jumping around on floating platforms outdoors, as one does in a Super Mario game, is perfectly normal. Jumping on couches and tables in someone’s carefully composed house is, at the very least, subverting expectations. A character that knocks into a virtual prop (or gets stuck in its geometry—an occasional buggy event in which two different objects occupy the same virtual space)—is not just a glitch in the software, but can also be interpreted as a social faux pas. Sure, conjuring a virtual antique wardrobe out of thin air might be easier than hauling a real one up a flight of stairs, but the end effect—of making a player feel like they are in a space that belongs to someone—is comparable.

These modes expand role-playing elements of video games beyond the character itself. Expression that was once limited to giving the main character a custom name (in Pokémon, for example) has branched out past the person into their space as well. "People like to embody their character," the YouTuber DarthXion, who specializes in videos showcasing design modes and whose real name is Dan, explains, "especially when they can design and create whatever character they like and take that in whatever direction they want. They can do a similar sort of thing with the home that character has. And much like, I suppose, in real life, they can have a home space that reflects their personality."

For Assassin’s Creed Shadows players, the recently added hideout mode makes abstract improvements tangible. Over what the developers characterize as "a little over one acre of fully customizable land on which players are able to place buildings, pavilions, pathways, bushes, trees, ponds, mossy rocks, local flora and fauna, and countless other Japanese cosmetic elements," the player gradually assembles a squad of rogues and offers them a place to congregate. Building certain structures, such as a training dojo, allows the player character and their allies to bolster their skills. Rather than simply dumping skill points into a menu interface, characters become stronger when their homes become stronger, drawing a direct connection between quality of living and overall performance.

The mere existence of the hideout, even for players who don’t care about the minutiae of mossy rock placement, also incentivizes exploring other parts of the game’s expansive map. Crates and chests throughout the land contain decorations for the hideout, tying the player’s home to the rest of society. Armor taken from a foe and paintings taken from fortresses can be put on display. Upgrading the hideout with resources like wood and metal requires the player to scour the broader region. It’s not a particularly deep system, but it’s a symbiotic one. Searching elsewhere improves the home, and improving the home makes it easier to perform actions elsewhere.

For games about the unusually specific act of "picking up trinkets to take home," the games of Bethesda Game Studios are in a class all by themselves. Titles in the Elder Scrolls and Fallout series of RPGs let players pick up basically anything smaller than a piece of furniture. Mugs, teddy bears, microscopes, pieces of fruit, slabs of meat, rusty cans, and thousands of other items. In earlier titles from the studio, these items could then be sold for money, or placed inside the player’s home, once it was purchased with said money. In later games, junk can be broken down into scrap components (a broken coffee cup can be scrapped for a few units of ceramic; a baseball mitt for leather, and so on) and then reconstituted into other structures, furniture, and props. "The Bethesda stuff is interesting because I think they sort of solved a problem that they had," DarthXion notes, "in that they had littered their world with a bunch of mostly useless junk that you could pick up, and there was nothing to do with it."

The system of accruing miscellaneous junk is something of a trademark for the developers. Todd Howard, Bethesda Game Studios’ longtime creative force, noted as much when promoting Starfield. "We like having all the coffee cups. We like being able to touch everything," he said in 2021. "Those moments make the whole thing believable." The ability to manipulate any small object doesn’t really have any narrative heft in the traditional sense, but it allows players to encounter and engage with what is known as environmental storytelling, conveyed through inanimate objects. A cliché example might be a room containing a corpse, a gun, and a note saying "goodbye, cruel world." You can put the three of those together to figure out what might have occurred. In Bethesda’s fantasy games, a wizard’s shack, full of 1,000 wheels of cheese, might not have a traditional story arc, but it definitely tells a story.

All of these home-design modes might not exist at all, however, without the field of video-game streaming. Much like how HGTV shows and Zillow listings give viewers an opportunity to drool over (or ridicule) someone else’s house, video-game streaming provides the same dynamic for virtual spaces. YouTube and TikTok feature a never-ending font of video-game home tours, which complicates how players interact with these spaces as they balance three different concerns: the motivation of the character (would my character own this chair?), the motivation of the player (do I like this chair?), and the interests of viewers (is this chair interesting enough for the For You algorithm?).

DarthXion says that even if YouTube didn’t exist, he would still be enamored with the building mode in Fallout (it took him exponentially longer to finish the main narrative of Fallout 4 because he kept getting sidetracked). But the video platform also motivates him to keep going back. On the one hand, viewers like to see novel finished products. Imagine an Architectural Digest "Open Door" not of a celebrity’s house, but one that belongs to a ghoul with rotting flesh. His audience, he says, likes "getting a few ideas and ... looking for inspiration."

They also need help learning precisely how to make those ideas a reality, so building tutorials come in handy too. Whereas real-life, Bob Vila-style content might teach viewers how to place an anchor in order to hang a shelf in their actual home that exists in physical space, video-game crafting tutorials might explain how to use quirks in the game’s code to create floating platforms and rooms.

The growing complexity of home-design systems, incorporated into more theatrical games with larger deliberate narratives, can surely be taken as a sign of demand. A simplistic read might focus on demographics—the most avid game players tend to skew younger amid an ongoing affordability crisis in homeownership and urban rental markets with low vacancy rates, and as gaming has grown broader, there are more opportunities for games that are less stereotypically masculine and focused on violence and destruction. If you can’t actually afford to decorate your living space (or don’t care to improve one belonging to your landlord), maybe you can experience fulfillment in a simulacrum. Putting that aside, the clearest reason for the proliferation of the design mode is that it allows players to engage with the game on a deeper level. There’s something to be said for participatory world-building, in which a player is able to literally construct their surroundings, one carefully placed sofa at a time.

Top photo of a SimCity Societies demonstration in 2007 by Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe/Getty Images.

Related Reading:

You Can Build Anything in the Metaverse, Especially a Déjà Vu-Inducing, Unlivable House

The Designers Using the "The Sims" as Architectural Software

No comments:

Post a Comment